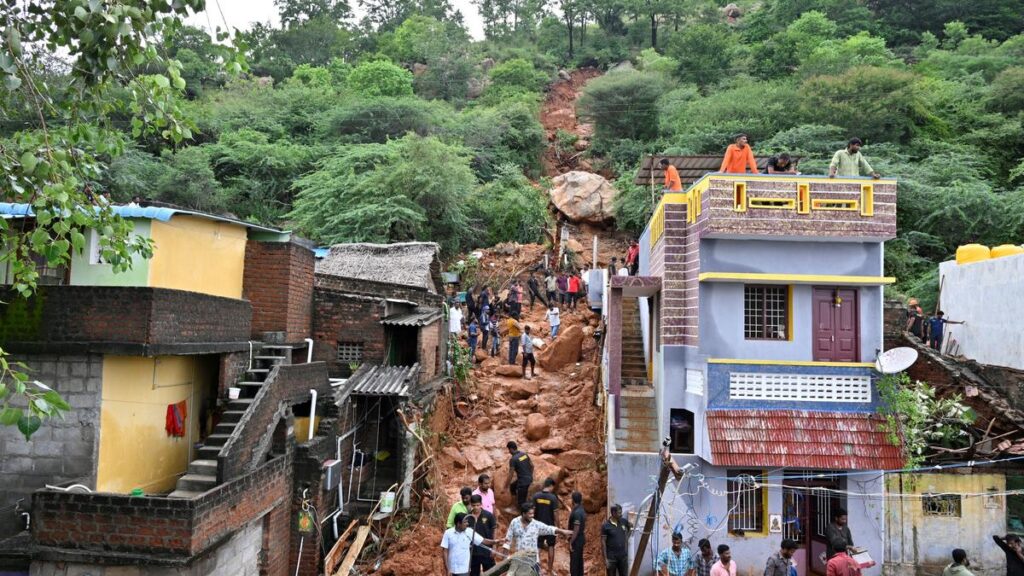

On the evening of December 1, 2024, a family of four and three of their neighbours huddled together under a metal roofed single-room house, in VOC Nagar, a residential area at the foot of the Arunachala hill in Tiruvannamalai district. They listened as torrential rains brought by Cyclone Fengal pounded the district in interior Tamil Nadu.

S. Meenakshi, 27, who lives opposite the house, recalls the tragedy that occurred shortly after. Her sister, R. Meena, 26, and Meena’s husband, N. Rajkumar, 32, both brick kiln workers, had returned home the previous evening as their workplace, located 20 kilometres from the temple town, had flooded. Meenakshi says the couple had been working in the brick kiln for a few years and had often stayed there for weeks to complete tasks before returning to VOC Nagar.

That Sunday was special for Rajkumar as he had come back to his children — 9-year-old Goutham and 7-year-old Iniya — after working tirelessly for a month at the kiln, she says. Meenakshi’s daughter, Ramya, 13, had also gone to Rajkumar’s house along with two neighbours — Vinothini, 14, and Maha, 10.

“Around 4.30 p.m., we heard a deafening sound. Meena called out to me and I rushed out,” says Meenakshi. “The next few moments were a blur. A heap of mud, boulders, and debris came rolling down the hill. Meena rushed inside to bring the children out but it was too late. My sister’s home was buried,” she says, sobbing.

All the seven occupants were instantly killed. Other houses in the neighbourhood were completely or partially destroyed. Relatives searched for loved ones in the slush amid relentless rains until a rescue team, led by Tiruvannamalai Collector D. Baskara Pandian, reached the site. They evacuated nearly 250 families from the hills, moved them to community halls in Tiruvannamalai town, and gave them food and medicines.

The seven bodies were recovered after a nearly 20-hour operation by a 170-member team, including 35 personnel of the National Disaster Response Force, and a sniffer dog the next evening. “When the team retrieved two bodies from the spot, they saw that Rajkumar had been holding Iniya tightly,” recalls a senior official.

A trail of destruction

While heavy rainfall during the northeast monsoon is common at this time of the year in Tamil Nadu, the State and the Union Territory of Puducherry did not expect Cyclone Fengal to cause such widespread devastation when it crossed the eastern coast on the night of November 30, 2024. On December 1, 2024, unusually heavy rainfall (40 cm to 50 cm) was recorded in many places in Puducherry and the northern and northwestern parts of Tamil Nadu. Among the coastal districts, Chennai was less affected.

The cyclone then slowly drifted westward, dumping rains, causing floods, submerging acres of crops, damaging civic infrastructure, and displacing thousands of people. When it later moved inland, it pummelled several districts. Mailam in Villupuram district received 51 cm of rainfall on December 1 and Uthangarai in Krishnagiri district received 50 cm on December 2. Some areas of Villupuram such as Kedar and Soorapattu received more than 33 cm of rainfall on a single day.

Widespread floods hit Uthangarai, Pochampalli in Krishnagiri

D. Vasanthkumar, 51, of Muthu Nagar in Nellikuppam, Cuddalore district, spent an entire night on the stairway leading to his terrace as floodwater had entered his house. “Local officials gave us flood alerts at 8 p.m. asking us to evacuate the street. But the water level rose rapidly in the area and a few of us were stranded. It took two days for the floodwater to recede,” he says. While Vasanthkumar managed to salvage important documents that were lying in his loft, he lost most of his electronic devices.

In his letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi this week, Chief Minister M.K. Stalin said 12 lives were lost in the cyclonic storm that had wreaked havoc in 14 districts. Villupuram, Tiruvannamalai, and Kallakurichi received more than 50 cm of rainfall in a single day, which was equal to an entire season’s share. He noted that more than 2.11 lakh hectares of agricultural and horticultural land had been inundated and nearly 963 cattle had died. About 9,500 km of roads, 1,847 culverts, and 417 tanks had been damaged. Stalin said that the cyclone had overwhelmed the State’s resources and requested the Centre to release ₹2,000 crore from the National Disaster Response Fund to assist rehabilitation efforts.

Besides compensation for damaged crops, the Tamil Nadu government announced relief of ₹2,000 per family in the districts of Villupuram, Cuddalore, and Kallakurichi on December 3. Stalin also donated one month’s salary towards the Chief Minister’s Relief Fund to execute relief measures in the six worst-affected districts. On December 6, the Union Home Ministry approved the release of ₹944.80 crore to the Tamil Nadu government as the Central share from the State Disaster Response Fund to help the people affected by the cyclone.

Puducherry Chief Minister N. Rangaswamy announced relief assistance of ₹5,000 to all ration cardholders affected by the cyclone in the UT and ₹30,000 per hectare to affected farmers.

Vehicles in the Uthangarai area of Krishnagiri following heavy rainfall on December 2, 2024.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Crops under water

Four days after the rains subsided, Villupuram, a predominant agricultural district, is struggling to return to regular life. Nearly 80,520 hectares of crops are damaged, many lakes have breached their banks, and the Malattaru and Then Pennai rivers are brimming with floodwater.

V. Tamilarasi, 64, of Pillur village in Villupuram taluk, is searching for someone to help her clear the deposits of sludge that cover her agricultural land. Flash floods in the Then Pennai river submerged crops. She has also lost two goats.

“I cultivated black gram and casuarina plantations in three acres. The crop is submerged under six feet of water. I spent ₹2 lakh for cultivation. I don’t know how I am going to manage the loss,” she worries.

Villages such as Pillaiyarkuppam and Arasamangalam have become small islands. They did not have power and communication networks for three days, which left many stranded or confined to their houses without water or food.

“The district previously experienced such large-scale floods in 1972. This time, I was caught unawares. While village administrative officers helped us, officials and elected representatives came much later,” Tamilarasi says.

The situation was no different in the urban stretches of Villupuram. S. Neela, 55, of Ashakulam, spent nearly a day cleaning the muck and waste that floodwater had brought into her house on December 1.

“Our street had waist-deep water. My family of four managed with 20 litres of packaged water for three days. We had to put up with the sewage that had mixed with the stagnant water for three days. We all worked together to drain the water as we didn’t get immediate help,” she says.

R.T. Murugan, district secretary, Tamil Nadu Vivasayigal Sangam (All India Kisan Sabha), says, “Crops in various parts were on the verge of drying for want of water until the downpour. We have not seen such water flow in the Malattaru and Then Pennai rivers in December. I was preparing for paddy harvest for Pongal and recently sowed black gram in an acre. I face a loss of ₹50,000 as floodwater marooned my land. Poorly maintained water bodies in villages too led to quick damage.”

Several residents say they want Villupuram to be declared as a disaster-affected district.

Floodwaters in Puducherry

Puducherry heaved a sigh of relief after the storm passed through the region on December 1, but was hit by another disaster when water was discharged from the brimming dams of Tamil Nadu, particularly the Sathanur dam in Tiruvannamalai on December 2.

The discharge of 1.68 lakh cubic feet per second (cusecs) of floodwater from the Sathanur dam sparked a political debate. The Opposition parties blamed the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam government for the deluge in the northern districts without prior notice. Refuting the claims of a self-created disaster, Water Resources Minister Duraimurugan noted that sufficient flood warnings had been given and flood discharge was planned considering the safety of the dam and the lives of the people.

The Water Resources Department noted that uncontrolled Thenpennai river catchment worsened the flood situation. Record-breaking rainfall in Krishnagiri and flash flood in tributaries such as Koraiyar and Kallar accelerated flow in the river that was already in spate. There is no mechanism to gauge rainfall or the floodwater generated in the Then Pennai’s tributaries.

A senior Water Resources Department official says Sathanur reservoir received an inflow of 40,000 cusecs within four hours from December 1 night. The reservoir did not have sufficient storage capacity to store the entire inflow, he adds. “We adhered to the rules and there was no lag in flood warning. After 1972, when the dam discharged nearly 2.57 lakh cusecs, this is the second time that such a high quantum of surplus water was released,” the official says.

However, G. Jayakumar of Pananhuppam, Villupuram district, who helped people reach relief camps, says, “Flood warnings did not reach the villages (A.K. Kuchipalayam and Kallipattu) close to the riverbanks. Residents assumed it would be another normal rain spell. Many left behind their belongings and cattle to save their lives.”

When the Water Resources Department team visited Villupuram, they were aghast at the damage. “We could not identify boundaries of water bodies and roads. The district is generally mostly dry in December. The teams are now assessing the damage,” the official says.

In Sathanur village, S. Arul, president of the village panchayat, rescued several elderly residents from huts that were submerged in floodwater and shifted them to a school. “They also lost important documents in the floods,” he says.

Predicting the path of a cyclone

Many officials say it is difficult to be fully prepared for a cyclone that causes such extensive damage. This is especially because it is difficult for weather models to pick up extreme weather events at a particular place, according to meteorologists.

Cyclone Fengal remained a low-pressure system after forming in the far eastern Indian Ocean on November 14 and became a depression in the Bay of Bengal only after 10 days. It moved relatively slowly for another week before the India Meteorological Department (IMD) said it had become a cyclone. On November 28, the IMD announced that Cyclone Fengal would cross the north Tamil Nadu-Puducherry coasts on the morning of November 30. The cyclone moved at a leisurely pace. While fast-moving cyclones tend to retreat quickly, slow-moving ones weaken into a deep depression, dumping unprecedented amounts of rainfall.

S. Balachandran, Additional Director General of Meteorology, Regional Meteorological Centre, Chennai, says the cyclone had undergone changes in its intensity over the ocean due to multiple factors. “The Regional Meteorological Centre had given sufficient forecasts and rainfall alerts for north Tamil Nadu on November 30 and December 1. Most of the forecasts were accurate. But in Krishnagiri and Dharmapuri, the prediction on rainfall intensity went off the mark,” he says.

The storm remained stalled over the ocean for six hours. It moved slowly towards the north and then slightly towards the east before moving towards the west and crossing the coast.

“The reason for the cyclone remaining stationary is a bit obscure and there are no immediate explanations for it,” says Y.E.A. Raj, former Deputy Director General of Meteorology, Chennai. “Though the clouds associated with the cyclonic storm were floating over the land, the centre of the cyclonic storm was close to the ocean and was able to draw a lot of moisture from the ocean. Since it got fed with all that moisture, it retained its intensity. This triggered a high amount of rainfall.”

Pointing out that the global warming and climate variability are likely to increase such unpredictable local weather patterns, G. Sundararajan of Poovulangin Nanbargal, a group advocating environmental protection in Tamil Nadu, says, “There is an urgent need to bridge gaps in last mile communication on flood warnings and weather alerts. We also need to map landslide susceptibility in all the districts so that we are better prepared for such disasters.”

lakshmi.k@thehindu.co.in; madhavan.d@thehindu.co.in

Published – December 07, 2024 03:00 am IST